The College of Design was awarded UK Sustainability Challenge Grants in 2022 and 2023 to document the adaptive reuse of the Gray Design Building and preserve the building’s history through documentation, education, and interpretation — from its start as a tobacco warehouse through its varied occupations by University programs to its current use as the new home for the College of Design and the Department of Landscape Architecture.

Gray Design Building Documenting Change

Project Goals

- Document and archive the history, evolution, and adaptive reuse of the building.

- Create and curate content for educators and the community focused on sustainability, adaptive reuse, and historic preservation.

- Disseminate information through online resources and interpretive integration into the new building.

In addition to archival research, photo documentation, site assessment, and 3D digital site models created using LIDAR, Documenting Change also developed a series of learning modules on sustainability, historic preservation, and documentation, as well as articles about the people and products involved in the project.

Historical Photos

Construction Photos

Learning Modules

Lesson One: Site History and Adaptive Reuse

|

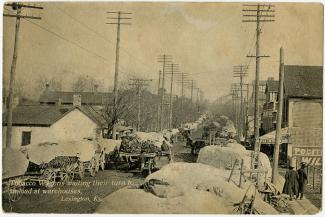

Aerial view of the Reynolds Building site (outlined in yellow) in Lexington, KY. |

Exterior view of the former Reynolds Building in 2019, before construction began. |

Rendering of the main entrance and covered outdoor workspace in the Gray Design building. |

by Emily Bergeron

Founded in 1865 as a land-grant institution, the University of Kentucky is the state’s flagship university. The campus is adjacent to downtown Lexington, Kentucky, a mid-sized city confined by an urban growth boundary created to protect the region’s famous horse farms and Bluegrass landscape. The University’s campus covers more than 918 acres, serves more than 30,000 students, and employs approximately 13,500 people. It comprises more than 19 million gross square feet of building space in more than 400 buildings (UK Sustainability Strategic Plan, 2018). Sitting on the west edge of campus on South Broadway is the R. J. Reynolds Company Building (“Reynolds Building”), a two-story, brick masonry building with heavy timber framing built in 1917 as a tobacco warehouse and redrying plant (Vivian, 2019). This historic site is the subject of Documenting Change.

The Reynolds Building has deep roots in the history and culture of the Bluegrass region. Lexington played a significant role as a tobacco market during the early twentieth century, and redrying plants like the Reynolds Building were common wherever tobacco auctions occurred. An extensive site history and conditions assessment by Historic Preservation Professor Dr. Dan Vivian details how the building existed before the August construction. The Reynolds Building had open interior volumes on all floors with wood columns and exposed trusses, creating a visual rhythm. The condition of the building’s large timber posts reflects a long history of use. Interior features continued to reflect past occupants, including interior partitions from the offices used by the original Reynolds Company staff, bead board wainscoting, hardwood doors, and decorative trim work.

The University of Kentucky acquired the Reynolds Building in the 1960s, using the new acquisition as the University’s art department (Kast, 2022). The School of Architecture was briefly housed in Building #1 before moving to Pence Hall. Since then, the buildings have been primarily used for storage and art studio classes, including sculpture, photography, metalworking, painting, and videography. The building was vacated about a decade ago when the University’s School of Art and Visual Studies relocated to a nearby adaptively reused historic tobacco warehouse. Leadership in the College of Design, seeking to find a space to unify all its programs under one roof, began surveying options. In February 2019, the University of Kentucky Board of Trustees approved the design phase for rehabilitating the Reynolds Building as the future home for the College of Design (UK College of Design, 2020). The University released plans for updating the building in 2021, including outdoor spaces, a cafe, and lecture halls utilizing student-designed furniture (Kast, 2022). The proposed adaptive reuse plans will take advantage of the structure’s existing layout. For example, open floor plans will use the “repetitive structural grid” to create a space that provides more opportunities for collaboration and experimentation (Wilson, 2021). On August 8, 2022, the University of Kentucky held a ceremonial groundbreaking for the Gray Design Building.

Using the Site as a Learning Laboratory

During the fall semester of 2022, the students of HP 252, Adaptive Reuse and Treatments for Historic Buildings, used the Reynolds Gray building as a field study to learn about traditional building structures, materials, and conservation techniques. Working with CPMD Project Manager Keith Ingram, Turner Construction, and Director of Technology and Facilities for the College of Design Joe Brewer, the class assessed the building in its (relatively) untouched state.

Students were asked to document the structural and material condition of the building before any major renovations occurred. The class will create a conditions assessment of the building that can be used to document the state of the Reynolds Building as it existed in August of 2022. This will provide contrast to the condition of the Reynolds-Gray Design Building after renovations are completed.

Why is this “sustainable”?

We have the ability and responsibility to minimize the climate impact of the structures we design. Circular strategies (e.g., adaptive reuse, refurbishing existing buildings, reuse of Second Life Components) are receiving increased attention as we recognize the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs). Adaptive reuse projects also have multiple other benefits, including the preservation of buildings and places with historical or cultural significance and reduced costs relative to new construction. Further, a successful adaptive reuse project often results in comparable performance to new “green” buildings without the added expense and emissions outputs involved in construction. Universities seeking to significantly reduce their carbon footprints are increasingly utilizing strategies that include retrofitting, renovation, and adaptive reuse (Jensen & Bergeron, 2022).

In the process of reimagining and adaptively reusing the space for the College of Design, the Reynolds/Gray project embodies the University of Kentucky’s mission to “design, construct, operate and maintain spaces that support the mission of the University while promoting environmental stewardship and the well-being of the community.” (UK Sustainability Strategic Plan, 25). Adaptive reuse, the reusing of an existing building for a new purpose instead of new construction, can significantly reduce embodied carbon impact and plays a role in a circular economy. The adapted building is 13500 m2 with an estimated CO2-eq per m2 per year of 9,191. A similar functioning new structure (only materials) would have a climate footprint of 124078 CO2-eq. The avoided CO2 emission by deciding to adapt is challenging to calculate precisely because the amount of removed material and environmental impact of new material is necessary to the calculation. As the project continues, this estimate will be easier to determine.

Studio Gang, the Design Architecture firm on the Reynolds/Gray adaptive reuse project, have noted the significance of the undertaking to sustainability:

When it is essential to conserve resources and decarbonize, reinventing existing buildings to serve new purposes has never been more critical. This project for the University of Kentucky College of Design (CoD) demonstrates how the act of fabrication can resonantly bridge between old and new as it transforms a century-old tobacco warehouse into a 21st-century, cross-disciplinary learning environment (Studio Gang, 2022).

Buildings are agents of change for environmental conservation. They can play a significant role in addressing climate and reducing GHG emissions. We are all consumers and occupants of buildings; however, we rarely actively think of the global environmental impact of where we live and work. While there is a bias towards appreciating what is “nice and new,” an adaptively reused building can serve as an example of sustainable design, inform inhabitants, and encourage social responsibility. Understanding the nature of sustainability, how the built environment affects the natural one, and what role we can play in making an impact through preservation and design is vital to creating a habitable planet. In the next module, we will look at the concept of sustainability, its origins and evolution, and what it means to be “sustainable.”

Suggested Readings

- “University of Kentucky College of Design.” Studio Gang, n.d. https://studiogang.com/project/UK.

- Vivian, Daniel, and Lily Hutzell. Working paper. Reynolds Building Historical Analysis and Inventory of Significant Features. Lexington, KY, 2019.

Lesson Two: Defining Sustainability

by Emily Bergeron

These days we can’t seem to escape the term “sustainability.” Making it through the day without encountering the word has become challenging. We shop for sustainable foods produced by sustainable agriculture. We see ads for sustainable energy sources and environmentally friendly public transportation. We are told to use reusable shopping bags, aluminum water bottles, and silicone straws. From head to toe – even fashion choices have become something that should be sustainable – how we wash our hair, the jeans we wear, even the shoes we run in.

Many indict sustainability and sustainable development as simple terms that mask real environmental problems by focusing on economic growth. Environmentalist Bill McKibben has called “sustainability” a “buzz-less buzzword” that was “born partly to obfuscate.” While it is trendy to be sustainable, this doesn’t mean the term is without merit – governments, communities, organizations, and individuals have tried to align themselves with its basic principles to create a safe, prosperous, and ecologically minded society. Much like the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions changed our lives – so might a sustainability revolution.

A Google search for the term “sustainability” returns around 2,210,000,000 results. Unfortunately, sustainability is often thrown around without fundamental understanding or substance. People use it to address issues including, but not limited to, climate change, infrastructure, architecture, energy, and more. These are essential steps in individual actions like using solar panels, recycling, and rainwater collection. But there is much to what it means to be sustainable.

“Sustainability” concerns systems and processes that can operate and persist independently over long periods. They can endure without failing. It comes from the Latin “sustinere – to maintain, support, endure.” There is also a German equivalent, Nachhaltigkeit – which first appeared in the literature in a 1713 forestry book by Hans Carl von Carlowitz, which described how the sustainable management of timber would allow the resource to be available indefinitely.

Sustainability evolved from many other ideas relating to the environment, its management, and protection. It begins with the concept of conservation (environmental, not heritage) – that nature (and specific elements) is a resource that must be managed. This differs from ecology – the late 19th and early 20th-century idea that relationships and connections in the larger environment must be considered. The environmental movement began in the 1960s and 70s. It is often associated with the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. The book’s title references a world without birds – the potential outcomes of indiscriminate pesticide use. The work introduced citizens to the problems with the environment to help them become actively engaged. In 1968, Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb, which addressed the issues of exponential growth.

The 1970s would be a good decade for environmental protection. The first earth day was held on April 22, 1970, and the event spoke to the need to address technology and alternative energy as part of the conversation. The 1970s was also a period in the U.S. when environmental legislation became a more central aspect of the federal regulatory environment. Laws enacted in this decade included NEPA, the Clean Air Act, the EPA was created, the Water pollution control act, Safe Drinking Water Act, Energy Policy and Conservation Act, National Energy Act, Federal Pesticide Control Act, Toxic Substances Control Act, Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, and the Endangered Species Act. During the 1960s and 70s, there was a growing awareness of distributional disparities and environmental justice.

Sustainability emerged as an environmental, social, and economic ideal in the late 70s and 80s. The term sustainable development was introduced in a 1980 report (“World Conservation Strategy”) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) – the term was later popularized in 1987 in the World Commission on Environment and Development’s (WCED) report known as the “Brundtland Report” or Our Common Future. This report defined sustainable development as “development that needs the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” It is also intended to recognize the rights of all people – including future generations. By the 1990s, the term sustainability had become familiar in politics – e.g., President Clinton’s Council on Sustainable Development. The concept of the “triple bottom line” (i.e., Environment, economics, equity. People, planet, profit) came about in 1997 from John Elkington.

Why do we Need Sustainable Practices?

“Sustainability is meant to counteract a moribund economic system that has drained the world of many of its finite resources, including fresh water and crude oil, generated a meltdown in global financial systems, exacerbated social inequality in many parts of the work, and driven human civilization to the brink of catastrophe by unwisely advocating for economic growth at the expense of resources and essential ecosystem services.” (Mason, P. 2010. The End of the Age of Greed. NY: Verso).

We face food scarcity, water depletion, pollution, habitat destruction, extinction, lack of renewable and nonrenewable resources, climate change, social inequity, failing governments, out-of-control corporate interests, and increasing wealth gaps. Species are declining, and natural disasters are out of control. We are at a tipping point. We have too much consumption and too much population growth. What happens when we cross the threshold?

Western cultures have operated with the belief that economic growth (and population growth), accompanied by constantly improving living standards (reliant on using various renewable and nonrenewable resources), can persist indefinitely. However, we are currently operating at over 140% of capacity. It is estimated we will be at 200% by the 2030s. This means human demands far exceed the regenerative capacities of the planet on which we live. We’ve depleted natural capital. We can only keep spending resources as slowly as they can regenerate.

Because all these things are connected, we cannot fix one problem in isolation. Sustainability is a holistic approach that addresses nearly 250 years of an unsustainable ecological assault created by industrialization. It is a way to recognize and address how we have created an imbalance. We cannot look at water problems – we have to look at how water problems impact many other issues. It also means we must have water quality engineers look at this issue. We need scientists and engineers, but also economists, educators, policymakers, and social activists to determine how we are to create safe, livable cities with plenty of green space, green buildings, public transportation networks, and agricultural systems that meet human needs without GMOs and monoculture, and water free of pollutants.

In other words, sustainability goes far beyond just environmentalism. It is about a balance between environmental, economic, and social well-being. These three are all connected – poverty, poor health, overpopulation, resource limits, and the degradation of the environment are all reliant on each other. It would be best if you also thought of the human-nature connection in sustainability – all systems are linked – so let’s call them social-ecological systems.

Suggested Readings

- Smith, M. et al. (2017). “Integration: the key to implementing the Sustainable Development Goals,”Sustainability Science, Vol. 12, No. 6, pp. 911-919

- UNESCO (2015). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

- Avrami, E. (2016). “Making Historic Preservation Sustainable,” Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 82, No. 2, pp. 104-112.

Lesson Three: Impacts from the Built Environment

by Emily Bergeron

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (I.P.C.C.) has attributed climate change to the increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations. Methane and nitrous oxide concentrations have increased dramatically since preindustrial values, and carbon dioxide emissions have risen more than 70% since 1970. The building industry is the most significant contributor to this rise in carbon dioxide, both directly and indirectly.

Buildings provide us with shelter as well as places to work, sleep, eat, and play. We are affected by their form, color, materials, space, and style. They capture society’s cultural, social, and historical narratives, helping us remember, understand, and connect to our past. They also connect us to our community and to place. They are one of the most significant and costly products of human activity. Buildings have an enormous impact on our lives and, more broadly, on the environment and economy. Construction activities impact the environment throughout the life cycle of development. These impacts occur from initial resource extraction for materials through work on-site through the construction period, operational period, and to the final demolition when the life of a building ends. The industry contributes to climate change, air pollution, water pollution, habitat destruction, and landfill waste.

The life cycle of a building can be divided into the extraction of necessary raw materials, processing or manufacturing of construction materials and building components, transportation and installation of these materials, operation, maintenance, and repair of the building, and demolition and disposal at the end of the lifecycle. Each phase places demands on and impacts the environment. So what exactly are the effects of construction?

Emissions

Building materials like concrete, brick, steel, aluminum, wood, glass, copper, asphalt shingles, and all sorts of plastics, from vinyl flooring to weatherproofing house wrap, all create greenhouse gas emissions. Steel and concrete, in particular, require heating raw materials to high temperatures, with the energy typically coming from fossil fuels contributing large amounts of GHGs. Cement for concrete is responsible for 7% of the world’s carbon emissions.[i] Steel creates 2.3 tons of carbon for every ton of metal produced.[ii]Aluminum is another high emitter, causing 3% of the world’s direct industrial CO2 emissions.[iii] Overall, 37 percent of energy and process-related CO2 emissions come from construction.[iv] In 2021, CO2 emissions from buildings reached ten gigatons, the highest level to date.

- Architecture2030

- Sizirici B, Fseha Y, Cho CS, Yildiz I, Byon YJ. A Review of Carbon Footprint Reduction in Construction Industry, from Design to Operation. Materials(Basel). 2021 Oct 15;14(20):6094. doi: 10.3390/ma14206094. PMID: 34683687; PMCID: PMC8540435.

- “How Much CO2 Is Emitted by Building a New House?”MIT Climate Portal.

- “The Construction Industry Remains Horribly Climate-Unfriendly.”The Economist, The Economist Newspaper.

- Environment, UN. “2022 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction.”UNEP.

Energy Consumption

The environmental impact of construction that accrues during the entire life cycle of a building includes energy consumption. According to the United Nations, the construction industry was responsible for 34 percent of energy demand and around 37 percent of energy and process-related CO2 emissions in 2021.[v]The U.S Green Building Council (U.S.G.B.C.) estimates are higher, placing the construction industry accounting for 40% of worldwide energy usage. Construction also accounted for 37 percent of “energy and process-related” emissions.[vi] At this rate, emissions from commercial buildings are expected to grow 1.8% in this decade alone.

In the United States, energy consumption by the residential and commercial sectors represents the majority of energy consumption in all U.S. buildings. Private households use this energy for space heating, water heating, air conditioning, lighting, refrigeration, cooking, and running appliances. The commercial sector broadly includes service-providing facilities and equipment for businesses, various levels of government, and other private and public organizations. The uses are similar to residential. In 2021, the combined residential and commercial end-use energy consumption approached 21 quadrillion British thermal units (Btus), or 28% of total U.S. end-use energy consumption.[vii]

Energy consumption during the construction of buildings needs to be better understood. The process from start to finish is fragmented and involves many parties.[viii] This makes it difficult to predict the energy required or its impact during construction. Although researchers often exclude the construction phase in determining lifecycle energy consumption, European and U.S. figures have estimated this portion to be about 7-10% of total embodied energy.[ix]

For more information on energy consumption, see:

- Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS)

- Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (C.B.E.C.S.)

- Manufacturing Energy Consumption Survey (M.E.C.S.)

- 2020 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction

- Shrivastava, S. And Chini, A. (2011). Estimating energy consumption during construction of buildings: a contractor’s perspective.

Pollutants and Waste

Materials used in and released during construction, from past and present, are known to cause harm to the surrounding environment – air, water, and land. Land clearing, diesel engine operation, demolition, burning, and working with toxic materials contribute to air and water pollution. Construction and demolition create windblown problems— fugitive dust— which can linger for days or even weeks. Dust and other emissions include toxic substances such as nitrogen and sulfur oxides. They are released during the production and transportation of materials and from site activities and have caused a severe threat to the natural environment (Spence & Mulligan, 1995; Ofori & Chan, 1998; Rohracher, 2001). Other harmful materials, such as chlorofluorocarbons (C.F.C.s), are used in insulation, air conditioning, refrigeration plants, and fire-fighting systems and have seriously depleted the ozone layer (Clough, 1994; Langford et al., 1999). Construction materials such as lead, volatile organic compounds, chromated copper arsenate, asbestos, silica, and polyvinyl Chloride (P.V.C.) are all pollutants associated with harmful health and environmental impacts. Noxious vapors also impact air quality from oils, glues, thinners, paints, treated woods, plastics, cleaners, and other hazardous chemicals. On-site negligence has also resulted in toxic spillages, which are washed into underground aquatic systems and reservoirs (Kein et al., 1999). In addition to toxins, construction sites also create much noise as workers use heavy machines and equipment and light pollution where new or temporary lighting may be installed, and large areas are floodlit.

The process also creates vast amounts of C&D waste comprised of building materials, construction debris, remodeling, repair, and demolition of structures. Specifically, steel, wood products, drywall and plaster, brick and clay tile, asphalt shingles, concrete, and asphalt concrete are used in the E.P.A.’s estimate of C&D debris generation. The agency determined that in 2018, the United States recorded 600 million tons of construction and demolition waste, making it the country’s most prominent individual solid waste stream.[x]Construction creates an estimated one-third of the world’s overall waste. Demolition represents more than 90 percent of total C&D debris generation, while construction represents less than 10 percent. Just over 455 million tons of C&D debris were directed to reuse, and just under 145 million tons were sent to landfills. Aggregate was the primary subsequent use for the materials in the C&D debris.[xi]

For more on pollution and waste, see:

- Akhtar A, Sarmah AK (2018). Construction and demolition waste generation and properties of recycled aggregate concrete: a global perspective. J Clean Prod 186:262–281.

- Wieser, A., Scherz, M., Passer, A, and Kreiner, H. (2021). Challenges of a Healthy Built Environment: Air Pollution in Construction Industry, Sustainability 2021, 13(18), 10469;

- “Sustainable Management of Construction and Demolition Materials.”EPA, Environmental Protection Agency.

Resource Scarcity

The construction industry uses more materials by weight than any other industry in the United States. More than 100 billion tons of raw material, the equivalent of two-thirds of the mass of Mount Everest, are removed from the planet every year.[xii] Half of that is sand, clay, gravel, and cement used for building. The E.P.A. has found that construction activity accounts for half of all the resources extracted from nature, one-sixth of global freshwater consumption, one-quarter of wood consumption, and one-quarter of global waste. Forty percent of these resources alone are turned into housing. Before the pandemic, consumption increased by more than 8 percent; however, the reuse of resources dropped from 9.1 to 8.6 percent.

For more on resource consumption and construction, see:

- Beatriz C. Guerra, Fernanda Leite, “Circular economy in the construction industry: An overview of United States stakeholders’ awareness, major challenges, and enablers,” Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Volume 170, (2021).

- Leonora Charlotte Malabi Eberhardt, Morten Birkved & Harpa Birgisdottir (2022). Building design and construction strategies for a circular economy, Architectural Engineering and Design Management, 18:2, 93–113, DOI: 10.1080/17452007.2020.1781588,

Biodiversity

The built environment is a significant driver of biodiversity loss. Biodiversity is the variety of life on earth — its ecosystems, habitats, and species. Development inevitably impacts biodiversity, destroying and diminishing habitats, ecosystems, and food sources. Development also impacts landscape connectivity, animal movement, and other ecological flows, inhibiting wildlife movement and their ability to meetbiological needs. This may lead to higher wildlife mortality, lower reproduction rates, smaller populations, and lower viability. More subtle impacts further down the line also result from these activities. For example, noise and light pollution during the construction process may disrupt species’ breeding and feeding behavior patterns and ultimately lead to population decline later. It may also lead a particular population to relocate to another area, reducing the biodiversity surrounding the development. Previously mentioned extractive practices to supply the materials needed for construction, such as timber, sand, and gravel, can alter or destroy habitats through removal. Additionally, noise, air, and water pollution can be secondary impacts. Converting raw materials for construction use creates even more pollution and waste and, by utilizing fossil-fuel-based energy sources, contributes to climate change, the single greatest threat to biodiversity.

For more on biodiversity, see:

- Biodiversity and the built environment: Implications for the Sustainable Development Goals (S.D.G.s), Alex Opoku, Resources, conservation and recycling, 2019 – Elsevier,

- Biodiversity: Built environment deep-dive

- Marzluff, John and Rodewald, Amanda (2008). “Conserving Biodiversity in Urbanizing Areas: Nontraditional Views from a Bird’s Perspective,” Cities and the Environment (CATE): Vol. 1: Iss. 2, Article 6.

[i] PBL Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving. “Trends in Global CO2 Emissions: 2016 Report.” PBL Planbureau Voor De Leefomgeving, 30 Aug. 2017.

[ii] “Mission Possible Sectoral Focus: Steel: ETC.” Energy Transitions Commission, 4 Jan. 2023.

[iii] Iea. “Aluminium – Analysis.” IEA.

[iv] Environment, UN. “2022 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction.” UNEP.

[v] “CO2 Emissions from Buildings and Construction Hit New High, Leaving Sector off Track to Decarbonize by 2050: Un.” UN Environment.

[vi] “CO2 Emissions from Buildings and Construction Hit New High, Leaving Sector off Track to Decarbonize by 2050: Un.” UN Environment.

[vii] Monthly Energy Review, Tables 2.2 and 2.3, December 2022.

[viii] Sharrard, A.L., H.S. Matthews, and M. R.O.T.H., “Environmental Implications of Construction Site Energy Use and Electricity Generation,” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, Vol. 133, No. 11, 2007, pp. 846–854.

[ix] Kohler. Life Cycle Cost of Building. in Buildings and the Environment. 1991. University of British Columbia; Cole, R.J. and D. Rousseau, “Environmental auditing for building construction: Energy and air pollution indices for building materials,” Building and Environment, Vol. 27, No. 1, 1992, pp. 23–30.

[x] EPA. “Facts and Figures About Materials Waste and Recycling.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency.

[xi] “Construction and Demolition Waste.” Environment.

[xii] PACE. “Circularity Gap Report 2021.” CGR 2021, 2021.

Lesson Four: Embodied Carbon

by Emily Bergeron

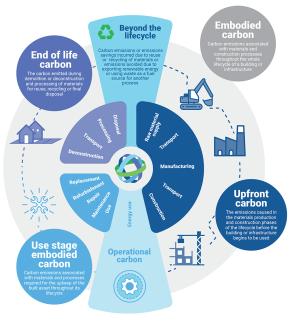

Every ton of carbon emitted stays in the atmosphere for hundreds of years; these emissions are cumulative. Buildings generate around 39 percent of annual carbon emissions worldwide. Twenty-eight percent comes from operating existing buildings, and 11 percent from new construction.[i] A significant cost to the built environment is embodied carbon. As the world’s population approaches 10 billion, the global building stock is expected to double in size, making understanding and addressing this issue of ’upfront carbon’ critical. In this lesson, we will look more closely at the emissions associated with the materials and construction processes throughout the lifecycle of buildings and infrastructure.

A building’s carbon footprint is composed of embodied and operational carbon. Embodied carbon is the CO2 created in producing building materials (e.g., materials extraction, transport to manufacturing, and manufacturing), transportation to the site, and during construction. It is also the carbon produced while maintaining and ultimately demolishing, transporting, and recycling those materials. Operational carbon comes from energy consumption – heat, lighting, etc. Embodied carbon is largely produced at the beginning of the building life cycle. These emissions are fixed, unlike operational emissions, which can be periodically altered by upgrading lighting, mechanical systems, or other equipment. Once a concrete foundation is poured, the carbon emitted during manufacture and transport can never be recovered.[ii]

Efforts to curb carbon emissions from building operations have shown some success – partly attributable to converting the grid to renewable power sources. Between 2005 and 2019, CO2 emissions from construction operations declined by 21 percent in the United States, even with an increase in total floor area.[iii] As we continue to reduce operational carbon, embodied carbon will account for a more significant part of buildings’ overall carbon footprint. Between now and 2050, it is anticipated that embodied carbon will account for nearly 50% of the overall carbon footprint of new construction.

Measuring and Calculating Embodied Carbon

Embodied carbon can be challenging to measure – having been called the building industry’s “blind spot.”[iv] This is partly because of a need for more agreement on measuring embodied carbon in buildings.[v] And a need for comprehensive data on the issue. Such emissions data on building operations is available, but currently, a government agency needs to curate this information. One generally accepted strategy for measuring is called life cycle assessment (LCA), which looks at the environmental impacts of a building from raw material extraction through end-of-life and disposal. Site activity emissions are also sometimes added to the calculation. The embodied carbon calculation typically multiplies the quantity of each material or product by a carbon factor (customarily measured in kgCO2e per kg of material) for each lifecycle stage being considered:

Embodied carbon = quantity × carbon factor

Project lifecycle showing both the scope of the definition and need for whole life consideration. From the report Bringing Embodied Carbon Upfront by the World Green Building Council.

Whole-Building Lifecycle

Materials Acquisition. Raw materials extraction, transport to process, process/manufacturing.

Construction. Transport to site, construction, and installation.

Use. Use, maintenance and repair, replacement, refurbishment, and operational use.

End of Life. Demolition, transport, waste processing, disposal, and recycling.

There are a variety of tools available to aid in collecting the data for these assessments: calculators, online or spreadsheet-based tools, which help determine the order of magnitude of embodied carbon early in the design stages before modeling begins, design-integrated LCA tools that allow you to calculate the environmental impacts of building material selections directly in a design model (e.g., Tally, a plug-in for Revit), product selection/procurement tools that collect product data and aid in comparing options, and professional LCA software.

For guidance on how to calculate embodied carbon, see:

- A brief guide to calculating embodied carbon

- Lewis, Megan, et al. Part II: Measuring Embodied Carbon – AIA.

Addressing Embodied Carbon

There are many ways to deal with the impact of embodied carbon. The AIA lists ten ways to reduce embodied carbon:[vi]

- Reuse buildings instead of constructing new ones

- Specify low-carbon concrete mixes

- Limit carbon-intensive materials

- Choose lower carbon alternatives

- Choose carbon-sequestering materials

- Reuse materials

- Use high-recycled content materials

- Maximize structural efficiency

- Use fewer finish materials

- Minimize waste

Suppose we are to reduce the emissions associated with the construction industry. In that case, it is critical that we improve building energy performance, decrease building materials’ carbon footprint, increase investment in energy efficiency, and be mindful of embodied carbon. For example, construction energy consumption could be addressed by changing how we produce materials. For example, with concrete, innovation could focus on lowering cement’s carbon footprint or finding an alternative. Cement kilns could utilize alternative methods for heating cement kilns rather than fossil fuels. Another possibility for reducing impact is recycling construction waste. Rather than the increased emissions that result from creating all new materials, projects can use recycled materials instead.

Another way that this aspect of construction’s carbon footprint is to utilize the existing building stock better. When you consider the amount of new construction projected and assume the role of embodied carbon, it is also vital that we look at existing building stock for adaptive reuse. Historic buildings have embodied energy that is lost when a building is demolished. According to a study commissioned by the federal Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP), about 80 billion BTUs of energy are embodied in a typical 50,000-square-foot commercial building, the equivalent of about 640,000 gallons of gasoline (ACHP, 1979). If a building is demolished rather than reused, that expended energy and carbon is essentially wasted, and even more is spent on the demolition process and new construction. In upcoming lessons, we will consider if old buildings can be as green as (or greener than) old ones.

For more on embodied carbon:

- Bringing Embodied Carbon Upfront

- The Reuse Imperative

- Saving buildings means saving carbon: how historic preservation fights climate change

[i] International Energy Agency, 2018 Global Status Report: Towards a Zero Emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector(Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme, 2018).

[ii] Amy Cortese, “The Embodied Carbon Conundrum: Solving for all Emission Sources from the Built Environment,” New Buildings Institute, February 26, 2020.

[iii] Architecture 2030, “Unprecedented: A Way Forward.”

[iv] Anthony Pak, “Embodied Carbon: The Blind Spot of the Building Industry,” Canadian Architect, July 3, 2019, 26–29.

[v] Manish K. Dixit, “Life Cycle Recurrent Embodied Energy Calculation in Buildings: A Review,” Journal of Cleaner Production (March 2018): 732.

[vi] Strain, Larry. “10 Steps to Reducing Embodied Carbon.” The American Institute of Architects.

Lesson Five: What is Historic Preservation and Why is it Green?

by Emily Bergeron

“Preservationists oppose the conventional American idea of consuming ever more… we are struggling to reverse the ‘use it up and move on’ mentality. We are moving in and picking up the pieces. We are taking individual buildings and whole neighborhoods that have been discarded and trying to make them live again. We are cleaning up after society’s litterbugs.”[1] Clem Sabine (1979).

According to the University of Kentucky College of Design’s website, historic preservation is:

An interdisciplinary field of study concerned with the care, use, and interpretation of historic buildings, sites, and landscapes. Preservation specialists study built environments considered historically valuable, assess their importance, and guide treatment, use, and interpretation decisions. Preservation professionals help communities determine what matters to them and why. The field encompasses everything from creative adaptation of older structures, interpretation of sites associated with historical atrocities, and restoration of examples of high-style architecture. Strong linkages to sustainability and social justice mean that historic preservation will play a vital role in debates about the future of communities worldwide during the coming century.[2]

The National Park Service defines the term as “a conversation with our past about our future.”[3] The National Trust for Historic Preservation ties “preservation” to the built environment, deeming it “the act of identifying, protecting, and enhancing buildings, places, and objects of historical and cultural significance.” The goal of historic preservation is to identify, designate, protect, rehabilitate, and maintain historic resources. In the United States, national, state, and local programs and nonprofit and grassroots organizations work to preserve historic structures, objects, sites, properties, and districts. Preservation operates across a spectrum of activities and typologies and can be defined in many ways depending on many variables.

“Preservation” in practice can range from the stringent levels of protection associated with preserving National Register-nominated sites to the adaptive reuse of historic building fabric. The former requires that modifications be subject to the standards for intervention known as The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties. The Secretary’s Standards provide guidelines for preserving, rehabilitating, restoring, and reconstructing historic buildings. These treatments define different levels of intervention:

- Preservation applies measures required to sustain a historic property’s existing form, integrity, and materials. It often focuses on ongoing maintenance and repair of historic materials and features rather than extensive replacement and new construction. Preservation retains the most significant amount of historic fabric and the building’s historic form.

- Rehabilitation entails a compatible use for a property through repair, alterations, and additions while preserving features that convey historical, cultural, or architectural values. This level accepts the need to alter or add to a building for continued use while maintaining its historic character.

- Restoration entails the removal of features added to a building from other periods in its history and reconstructing missing parts from the restoration period. It seeks to preserve materials, components, finishes, and spaces from a period of significance and remove those from other periods.

- Reconstruction is new construction that seeks to replicate the form, features, and detailing of a non-surviving site, landscape, building, structure, or object from a specific period and in its historic location.[4]

These guidelines provide historic building owners and building managers, preservation consultants, architects, contractors, and project reviewers with intervention standards before beginning work. The standard applied to a specific site should consider each project’s economic and technical feasibility. These standards are applied generally to designated properties, and modifications can require permission from a board of architectural review. This additional burden, however, comes with the added benefits of potential financial assistance in the form of state and federal tax credits.

Buildings whose existence has outlived their function, often commercial or municipal structures, may be adaptively reused to create new uses. There are adaptive reuse projects undertaken in Register-listed buildings that are subject to higher standards to qualify for tax credits, but not all adaptive reuses rise to this level. Adaptive reusemust find a balance between façadism, where the face of a building is preserved with a new structure built behind or around it, preservation, and new construction. The Grey Design Building is an adaptive use of a historic structure not subject to the Secretary’s Standards.

In an article for the National Trust, Julia Rocchi listed Six Practical Reasons to Save Old Buildings, identifying the cultural and practical value of old buildings and explaining why preservation benefits a community’s culture and local economy. Rocchi cites the following justifications:

- Old buildings have intrinsic value;

- When you tear down an old building, you never know what’s being destroyed;

- New businesses prefer old buildings;

- Old buildings attract people;

- Old buildings are reminders of a city’s culture and complexity; and

- Regret only goes one way.[5]

Rocchi’s list does a good job explaining the benefits of preservation to culture and economy. Still, the practice also has the potential to be an essential tool in sustainability and sustainable development. However, relatively new to sustainability, historic preservation did grow alongside the conservation movement in the United States. While the preservation movement started nearly half a century before the Sierra Club was founded, it is only relatively recently that the profession has considered the impacts of preservation more broadly to include environmental, economic, and social well-being as well as the negative externalities associated with “progress.” There were early links between disciplines, such as Preservation Brief 3 – Conserving Energy in Historic Buildings (1978). This publication recognized that buildings constructed before WWII often used less energy than those of the recent past. These older buildings addressed interior climate with lower energy consumption. Embodied energy was used to justify preserving buildings as early as 1979 in the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation’s publication Energy Conservation of Historic Preservation: Methods and Examples. The NTHP again raised the issue in the 1981 publication New Energy From Old Buildings.

Conserving buildings rather than demolishing and rebuilding them avoids energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, resulting from the embodied energy expended in providing new construction materials and components. The difference between operational and embodied energy was discussed in a prior lesson. Operational energy is created through the systems and practices used to operate the building. For example, heating and cooling systems contribute to this calculation. An environmental case may be made for new construction regarding the ecological impact of buildings – with their tighter fitting windows, central air conditioning, and other state-of-the-art systems. However, when you consider the effects of construction, the argument for preserving the existing building fabric becomes stronger.

Bypassing the wasteful process of demolition and reconstruction has significant environmental benefits, energy savings, and the social advantage of repurposing a place with a valued heritage. Even so, it is a common argument that existing buildings are drafty, old, and inefficient – not green. This is simply untrue. Although older buildings are dismissed as inefficient, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) data indicates that commercial buildings constructed before 1920 use less energy per square foot than buildings from any other decade up until 2000 (EIA, 2003).

This is because many of these structures were designed with passive systems before electric lighting and powered heating and cooling, taking advantage of natural daylight, ventilation, and solar orientation. These characteristics, now touted as “sustainable” design attributes, are historic building practices worthy of preservation. Older structures were also built with traditional, durable materials such as concrete, wood, glass, and steel, which, if properly maintained, have a long lifespan.

According to the US Green Building Council, “Green building is a holistic concept that starts with the understanding that the built environment can have profound effects, both positive and negative, on the natural environment, as well as the people who inhabit buildings every day. [It] is an effort to amplify the positive and mitigate the negative of these effects throughout the entire life cycle of a building.”[6] This idea of being “green” is readily applicable to historic preservation. Historic preservation serves environmental conservation purposes, addressing everything from embodied carbon to preventing the creation of construction debris. However, preservationist Norman Tyler labels buildings as “essential carriers of our community’s history,” adding an extra dimension to these profound effects on the people who inhabit them daily. In the next module, the concept of adaptive reuse as a strategy for preservation and sustainability will be elaborated upon.

For more on preservation as sustainability, see:

- Avrami, Erica. Preservation, Sustainability, and Equity. Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2022.

- Cooper, Deborah. “Reconciling Preservation and Sustainability | Architect Magazine.” Architect, 3 Feb. 2010, www.architectmagazine.com/technology/reconciling-preservation-and-sustainability_o.

- “Smart Growth and Preservation of Existing and Historic Buildings.” EPA, www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/smart-growth-and-preservation-existing-and-historic-buildings.

- Leifeste, Amalia, and Barry Stiefel. Sustainable Heritage: Merging Environmental Conservation and Historic Preservation. Routledge, an Imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, 2018.

- Libraries, University of Miami. “Historic Preservation (Sustainability) Research Guide.” Historic Preservation (Sustainability) | University of Miami Libraries, sp.library.miami.edu/subjects/HPsus.

- Longstreth, Richard W. Sustainability & Historic Preservation Toward a Holistic View. University of Delaware Press, 2011.

- McDonald, Martha. “Preservation and LEED See Eye to Eye – Traditional Building.” Traditional Building, 21 July 2015, www.traditionalbuilding.com/product-report/preservation-and-leed.

- Mohamed, Rayman, et al. “Adaptive Reuse: A Review and Analysis of Its Relationship to the 3 Es of Sustainability.” Facilities, 7 Mar. 2017, www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/F-12-2014-0108/full/html.

- “” National Preservation Institute, www.npi.org/sustainability.

- Technical Preservation Services. “” National Parks Service,www.nps.gov/orgs/1739/sustainability.htm.

[1] Clem Sabine, “Preservationists Are Un-American,” Historic Preservation(March 1979), p. 18.

[2] “University of Kentucky College of Design.” Historic Preservation – College of Design – 38°84° the Power of Place, design.uky.edu/historic-preservation/.

[3] “What Is Historic Preservation?” National Parks Service, www.nps.gov/subjects/historicpreservation/what-is-historic-preservation.htm.

[4] 36 CFR Part 68.

[5] Rocchi, Julia. “Six Practical Reasons to Save Old Buildings: National Trust for Historic Preservation.” Six Practical Reasons to Save Old Buildings | National Trust for Historic Preservation, 10 Nov. 2015, savingplaces.org/stories/six-reasons-save-old-buildings.

[6] “What Is Green Building?” U.S. Green Building Council, www.usgbc.org/articles/what-green-building.

Lesson Six: Adaptive Reuse

by Emily Bergeron

“The greenest building is the one that is already built.”

Carl Elephante

At times, preservationists have been criticized for protesting too strenuously against any change to historic resources. This tradition dates back to John Ruskin, who said, “No changing of place at a hundred miles an hour will make us one whit stronger, or happier, or wiser. There was always more in the world than man could see, walked they ever so slowly; they will see it no better for going fast. The really precious things are thought and sight, not pace. It does a bullet no good to go fast; and a man, if he be truly a man, no harm to go slow; for his glory is not at all in going, but in being.” In the past, this may have been true; however, it’s not necessarily a fair characterization of preservation today. Change is not only unavoidable; it can also bring benefits. By preserving and using the existing building stock, we can protect cultural values expressed through the built environment while still using what exists for development, giving buildings a new life and prolonging their lifespan.

Adaptive reuse is a form of historic preservation that recognizes the importance of more than protecting prestigious, monumental, or historically significant buildings. Old, sometimes abandoned, facilities exist across the country. Adaptive reuse allows us to breathe life into these structures – from warehouses to lighthouses – and give them a new purpose. “Adaptive reuse” is the process of repurposing an existing structure for a new use, an essential practice when you consider that structures often outlive their functions.

Building changes can involve major internal space reorganization and service upgrades or replacement. Alternatively, adaptive reuse may require minor restoration works where nothing changes except the building’s functional use. When applied to historic buildings like the Reynold’s Building (now the Gray Design Building), it retains the structure and conserves the effort and skill of the original builders.[1] as well as the place’s architectural, social, cultural, and historical values.[2] Reuse also speaks to the pillars of sustainability in that it improves material and resource efficiency (environmental sustainability), reduces costs (economic sustainability), and retains community infrastructure (social sustainability).

Good adaptive reuse respects and retains a place’s character-defining features while adding a new layer creates future value. With this, abandoned armories become shopping centers; churches turn into restaurants, schools into senior living communities, or tobacco warehouses into a College of Design. Adaptive reuse has been used for low-income housing, community centers, and mixed-use complexes. In 2040 approximately two-thirds of the global building stock will be buildings that exist today.[3]Understanding how adaptive reuse helps maintain cultural heritage by using historic architecture and restoring significant sites that might otherwise be left to deteriorate or be demolished, replaced with new buildings or parking lots. Saving buildings that are important to communities preserves a site and can be an essential part of a place’s social capital – providing economic, cultural, and social benefits to community members. This practice also helps to address sprawl – the creeping, unrestricted expansion of urban areas. Developers seeking sites for new construction are sometimes forced to use land outside city centers, increasing infrastructure costs and creating negative environmental impacts such as air and water pollution, dangerous traffic patterns, and social isolation.

Adaptive reuse, compared to new construction, can have financial advantages and cost savings. This recycling option generally uses more labor than building materials. While materials costs have increased significantly, labor costs have not risen at the same rate. This practice also eliminates the need for demolition costs. And, where specific standards are met for historic preservation, federal, state, and local tax incentives can reduce the cost of repurposing a building. New construction can also take longer than many adaptive reuse projects. Perhaps most importantly, communities benefit from and appreciate maintaining these buildings, which are important markers of history and culture. It is also an excellent strategy to promote sustainability, as reusing existing buildings eliminates some of the embodied energy and carbon costs associated with new construction.

Sustainable development requires the preservation, reuse, and “greening” of existing buildings to help reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions. Recall from an earlier module that old buildings contain embodied energy (i.e., the fuel and labor it costs to produce them – making and shipping the materials to assembling them on site). Adaptive reuse retains this energy by circumventing demolition and construction.

The US government estimates that approximately 1 billion square feet of existing building stock are demolished and replaced each year—adaptive reuse rather than new construction results in less debris in landfills and a healthier environment. Demolition profoundly impacts landfills; construction and demolition debris constitutes about two-thirds of all non-industrial solid waste in the US (EPA, 2010). The average building demolition results in 155 pounds of waste per square foot. A new construction project yields 3.9 pounds of waste per square foot of building area.[4] Even when materials are recycled, millions of tons of debris yearly end up in landfills. A 2004 Brookings Institution study indicated that if we continue with national development trends, by 2030, we will have demolished and rebuilt nearly one-third of our entire building stock — 82 billion square feet.[5] The energy required to accomplish this would power the state of California – 37 million people – for a decade.

Adaptive reuse occurs along a spectrum. Levels of intervention can be close to traditional historic preservation, maintaining as much of the structure as possible using minimally invasive mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP) upgrades and adaptations required to meet new building codes. These alterations are generally considered appropriate based on the standards created by the National Park Service.[6] This level does not allow the flexibility of using new, efficient materials while acknowledging the structure’s history. At the other end of the spectrum exists integration and façadism. The former involves building around an original design, preserving the structure, and encompassing it inside a new building. The latter maintains only the building’s facade while demolishing the bulk of the rest to replace it with a modern structure while preserving the street view. Preservationists generally favor neither of these interventions. Somewhere between these two extremes lies adaptive reuse like that undertaken in the Gray Design Building.

It is important to note that only some buildings are well-suited for adaptive reuse. Developers mustnavigate everything from building hazards to legal red tape. Problems may arise in meeting modern safety standards, land-use and zoning laws, and building codes, such as a lack of accessibility compliant with the Americans With Disabilities Act. Older buildings may also contain hazards such as asbestos, lead paint, and mold. These issues can be addressed during construction but must be considered in determining the feasibility of adaptive reuse.

Jane Jacobs, an activist known for her influence on urban studies, sociology, and economics in her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), argued that “urban renewal” and “slum clearance” failed to meet the needs of city dwellers. She sought instead to protect neighborhoods from the wrecking ball, recognizing the importance of architecture to a community. Jacobs stated, “Old ideas can sometimes use new buildings. New ideas must use old buildings.” Adaptive reuse allows communities to use old buildings for new ideas while also making a significant impact in meeting sustainability goals.

For more on adaptive reuse, see:

- Aigwi, Esther & Duberia, Ahmed & Nwadike, Amarachukwu. (2023). Adaptive Reuse of Existing Buildings as a Sustainable Tool for Climate Change Mitigation within the Built Environment. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments. 56. 10.1016/j.seta.2022.102945.

- Berkovitz, Nina. New Life for White Elephants: Adapting Historic Buildings for New Uses, Washington: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1996.

- Bottero, Marta & Datola, Giulia & Fazzari, Daniele & Ingaramo, Roberta. (2022). Re-Thinking Detroit: A Multicriteria-Based Approach for Adaptive Reuse for the Corktown District. Sustainability. 14. 8343. 10.3390/su14148343.

- Boyle, Jayne. Guide to Tax-Advantaged Rehabilitation, Washington: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2002.

- Brand, Stewart, How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built. London: Penguin Books, 1995.

- Bullen, P.A. and Love, P.E.D. (2011), “Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings,” Structural Survey, Vol. 29 No. 5, pp. 411-421. https://doi.org/10.1108/02630801111182439

- Bullen, P.A. and Love, P.E.D. (2011). Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings: Sustaining an icon or eyesore.

- Dedek, Peter, Historic Preservation for Designers. New York: Fairchild Books, 2014.

- Della Spina, Lucia. (2021). Cultural Heritage: A Hybrid Framework for Ranking Adaptive Reuse Strategies. Buildings. 11. 132. 10.3390/buildings11030132.

- Grabar, Henry. “What If Old Buildings Are Greener than New Ones?” Slate Magazine, 6 Dec. 2021, slate.com/business/2021/12/tulip-embodied-carbon-sustainability-old-buildings.html.

- Hutchins, Nigel, Restoring Old Houses, New York: Firefly Books, 1997.

- Jackson, Jason. “Neighborhood Revitalization through Culture, Community, and Creativity | Jason Jackson | Tedxmemphis.” YouTube, 20 Sept. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=XMF6FP2_jys.

- Kitchen, Judith, The Old-Building Owner’s Manual, Columbus: Ohio Historical Society, 1983.

- Merlino, Kathryn (2014). “[Re]Evaluating Significance: The Environmental and Cultural Value in Older and Historic Buildings,” The Public Historian, Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 70-85

- National Trust for Historic Preservation (2016). The Greenest Building: Quantifying the Environmental Value of Building Reuse, https://forum.savingplaces.org/viewdocument/the-greenest-building-quantifying

- Nelson, Arthur (2004). “Toward a New Metropolis: The Opportunity to Rebuild America” (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution), available at https://www.brookings.edu/research/toward-a-new-metropolis-the-opportunity-to-rebuild-america/

- Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties, https://www.nps.gov/tps/standards.htm

- Weaver, Martin, Conserving Buildings: A Manual of Techniques and Materials, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1997.

[1] Bullen, P.A. and Love, P.E.D. (2011), “Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings,” Structural Survey, Vol. 29 No. 5, pp. 411-421. https://doi.org/10.1108/02630801111182439

[2] McCoy, Nancy & Latham, Derek. (2001). Creative Reuse of Buildings. APT Bulletin. 32. 77. 10.2307/1504746.

[3] Lockwood, Charles. “Building the Green Way.” Harvard Business Review, 25 Aug. 2014, https://hbr.org/2006/06/building-the-green-way; “Why the Built Environment?” Architecture 2030, https://architecture2030.org/why-the-building-sector/.

[4] Sahabi, Ali. “Structural Retrofits Reduce the Carbon Footprint (Part 2 of 3) – USGBC-La.” USGBC, 25 Feb. 2023, usgbc-la.org/2023/02/09/structural-retrofits-reduce-the-carbon-footprint-part-2-of-3/.

[5] Nelson, Arthur (2004). “Toward a New Metropolis: The Opportunity to Rebuild America” (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution).

[6] National Park Service. Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties, available at https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1739/secretary-standards-treatment-historic-properties.htm

Lesson Seven: Documenting Change to Protect Our Heritage

Human-caused disasters, from war to uncontrolled development, natural disasters, neglect, and inappropriate conservation, all contribute to our vanishing heritage. Sometimes faster than we can record what exists. Maintaining a record of a site means that, no matter the future, people will be able to know what was once there. Therefore, an essential aspect of preservation, whether a building is to be restored, adaptively reused, or even demolished, is documenting the details of the historic property.

In documenting a site, Meghan White of the National Trust for Historic Preservation suggests we ask, “What could be lost? What are the materials that make up this structure? Where are the visible signs of craftsmanship? What elements are important to remember?”[1] According to the Getty Conservation Institute, documentation includes two main activities: “(1)the capture of information regarding monuments, buildings, and sites, including their physical characteristics, history, and problems; and (2) the process of organizing, interpreting, and managing that information.”[2] Collecting this information helps us assess the value and significance of the site in question; guide conservation, monitoring, and management efforts; create an essential record; and communicate the importance of a place.

Good documentation allows a better understanding of a site’s value—historical, scientific, aesthetic, social, and economic.

The information gained through documentation establishes a baseline, provides an idea about current conditions, informs appropriate conservation options, interventions, and treatments, and aids in assessing the results of efforts. It is the basis for monitoring, management, and routine maintenance and creates a record for posterity. It may also be the basis of nominations to the National Register of Historic Places or equivalent state or local registries in the United States. Documenting change is also essential. Heritage sites undergo continuous change; all interventions are critical moments in the life of a site. A record of these interventions is vital to preservation as actions become a part of a place’s history, and future generations benefit from knowing how preservation efforts (or adaptive reuse) were carried out. Documentation also creates information that can be communicated—to help educate the public on the value a site holds and how preservation has been executed.

Physical documentation might include measuring each elevation and noting character-defining features such as windows, ornament, doors, materials, form, etc. It may also include an analysis of the integrity of the building and materials, applying the National Register’s seven aspects of integrity (location, setting, design, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association). Documentation could include photographs and sketches. Technology plays a vital role in historic preservation. There are various methods of documenting historic sites, from hand measurements to more high-tech methods, like global positioning system (GPS) technology, ground-penetrating radar, light detection and ranging (LiDAR), and photogrammetry. These new technologies have reduced the time required to document heritage but can be costly and require specialized equipment and training.

Researchers may document and analyze the various materials and construction techniques and their conditions in historic properties. Considerations include materials (e.g., masonry; wood; metals), features (e.g., roofs; windows; doors; entrances/porches; spaces/features/finishes), and site and setting. Historical research may also be undertaken to document the history of the building, including people, functions, and changes. Historical contexts and narratives are also developed using primary source documents (e.g., deeds, trusts, wills, probate documents, genealogies, fire insurance maps, archival material, land and property records, census data, city directories, images, memorabilia, interviews, tax assessments, obituaries, newspapers, funeral directories, personal interviews, insurance records, etc.). A report discussing the history and historical context of the building is often produced, including photo documentation.

For more on digital documentation, see:

- Chhaya, Priya, and Reina Murray. “Forum Journal: Technology Transforming Preservation.”Preservation Leadership Forum, National Trust for Historic Preservation, 22 June 2018, https://forum.savingplaces.org/blogs/forum-online/2018/06/22/forum-journal-technology-transforming-preservation.

- TChhaya, Priya, and Reina Murray. “Technology and Historic Preservation: Documentation and Storytelling.”De Gruyter, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 4 Apr. 2022, https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110430295-021/html.

Historic American Buildings Survey

Internationally, standards for recording and documentation are only sometimes available. As a result, documentation can vary in form, quality, and quantity. In the United States, one established set of guidelines was created through the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS). This rigorous method of documentation was established in 1933 to document the country’s heritage and help to preserve a record of vanishing architectural resources. This system was intended to represent “a complete resume of the builder’s art,” – meaning it documents all types and styles, from the monumental and architect-designed to the utilitarian and vernacular.

HABS is a method of field investigation. Through hand measuring, or in the case of exceptionally large or inaccessible structures, three-dimensional laser scanning, measurements are recorded using pencil on graph paper. This data is supplemented by digital photography. Drawings are then produced using Computer Aided Drafting. In addition to the fieldwork, primary source research is conducted to create a written report outlining the architectural and historical context in which the structure was developed and evolved. Details and spatial relationships not easily conveyed by drawings or narratives are recorded using large-format, black-and-white photographs and supplemented with color photography. These various documentation methods create apermanent record that can be used to study and understand historic structures. However, the HABS documentation level is only sometimes appropriate or necessary for all historic buildings, sites, and landscapes.

For more about HABS, see:

- “Recording Historic Structures and Sites with Habs Measured Drawings: Heritage Documentation Programs–HABS, HAER, Hals, CRGIS–of the National Park Service.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/hdp/standards/HABS/HABSrecording.htm.

- “Photography Guidelines (HABS/HAER/Hals) – National Park Service.”National Park Service, Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/hdp/standards/PhotoGuidelines.pdf.

- Historic American Buildings Survey Guidelines for Historical Reports. National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/hdp/standards/HABS/HABSHistoryGuidelines.pdf.

- “Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey – about This Collection.” Library of Congress, 1 Jan. 1970, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh/ .

- “Webinar: In Pursuit of the Complete Resume of the Builders Art .”National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/hdp/webinar.htm.

Creating a Lasting Record

Archiving the data collected is important to making the documentation process impactful. Because technologies are constantly changing, it is also crucial to the documentation process that we ensure the long-term archival sustainability of what is created. There are always new ways to digitally store more information in varied forms — images, videos, and audio formats allow people to record more data and retrieve and examine it more efficiently. Further, the internet has allowed greater access to information and has provided researchers with a better way to distribute and share information. As technologies evolve, we must continue to be able to access the data so that we ensure that the record created by these new technologies is preserved in the long term.

Documenting the Gray Design Building

Various classes, faculty, and others have extensively studied and recorded the Gray Design Building. In advance of and during the adaptive reuse of the Building, additional extensive documentation efforts have been undertaken to create a record of what existed before construction and the construction process itself.

Documentation began with an evaluation of the physical state of the structure and all its architectural elements. A conservation team took note of each building material, its condition, its utility, and the way it interacts with other building materials to form the overall structure. The team rated every material by condition. Where material deterioration was evident, a sensitive conservation remedy was suggested. Structural systems were also identified and assessed, failures were identified, and reinforcement strategies were prescribed for stabilization. This documentation was compiled into a single document recording the state of the building at the time of assessment. Read the full report.

In addition to the conditions assessment, Light Detection and Ranging Scanning (LiDAR) has been used to scan the building to collect comprehensive data to create high-resolution 3D digital models. LIDAR can scan and model buildings for historical reference or information in specific renovation projects. This technology can be used to create interior and exterior scans of the Building. The data will then be processed into the project’s contiguous point cloud model. This data may later be used to create a virtual tour of the property by pairing utilizing the point cloud data and the RGB data associated with each point. LIDAR will be used regularly to document interior and exterior changes resulting from the adaptive reuse process.

The 3-D digital models of the building and landscape have been supplemented by digital documentary photography. Photographs of all sides of the exterior, exterior details, and overviews of the interior and interior details were taken before construction as permitted. Photography will continue during and after the adaptive reuse using hand-held cameras. (If you have any photos you might include from the documentation, that would be amazing)

The information will be available to faculty, students, and the community at large for teaching and research purposes in the future.

Additional Reading:

- “Historic Building Condition Assessment.”CA State Parks, State of California, https://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=24847.

- McDonald, Travis. “Understanding Old Buildings: The Process of Architectural Investigation.”S. Government Bookstore, 28 Mar. 2019, https://bookstore.gpo.gov/products/understanding-old-buildings-process-architectural-investigation.

- Letellier, Robin. Recording, Documentation, and Information Management for the Conservation of Heritage Places. Guiding Principles. 2007, https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/recordim.html.

[1] White , Meghan. “6 Tips to Document Historic Details before They Disappear: National Trust for Historic Preservation.” 6 Tips to Document Historic Details Before They Disappear | National Trust for Historic Preservation, 6 Dec. 2016, https://savingplaces.org/stories/6-tips-to-document-historic-details-before-they-disappear.

[2] LeBlanc, François, and Rand Eppich. “Documenting Our Past for the Future.” The Getty: Explore, The Getty Conservation Institute, https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/newsletters/20_3/feature.html.

Lesson Eight: Sustainability in Higher Education

Climate change demands a holistic response integrating policy, practice, and equity. As research and teaching institutions, universities play an essential role in responding to the complex challenge it represents. Universities have always been at the forefront of creating and breaking paradigms and educating future decision-makers and leaders. These organizations also have contributed significant emissions to the climate crisis. As the educators of future leaders and laboratories for experimentation, higher education institutions have an opportunity and a responsibility to help overcome these pressing challenges. Universities must lead in actions to limit climate change.

In 2005, the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education (“AASHE”), the first professional higher education association for campus sustainability in North America, was launched. The following year, presidents from a dozen US schools signed on to the American College and University Presidents’ Climate Commitment, setting a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions on their campuses; since then, more than 800 institutions have become signatories. Two years later, the AASHE piloted its first version of its Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System (“STARS”), a self-reporting framework for colleges and universities to measure their sustainability performance. These organizations seek to encourage campuses to address climate change by integrating resilience into their curriculum and research and through campus operations – including building operations, maintenance, design, and construction.

For more on Higher Ed Sustainability Organizations, see:

The Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education

The Presidents’ Climate Leadership Commitments

UNEP’s Sustainable University Framework

Efforts to make universities more sustainable fall under three categories: Research, teaching, and operations. Sustainability should be recognized as a tool to attract, retain and motivate top students and employees. Funding opportunities for research in the field come from entities ranging from the federal government to university seed grants in areas ranging from environmental science to historic preservation. The three pillars of sustainability – environmental, economic, and social well-being – lend themselves to broad research opportunities across campuses and provide excellent opportunities for trans-disciplinary research.

83% of Gen Z youth “worry about the planet’s health,” according to a 2021 NextGen Climate Survey. Regarding sustainability in higher ed, students expect the topic to be a part of their education. 75% of students say that an institution’s environmental commitment influences their choice of school, according to a survey conducted by the Princeton Review. Teaching sustainability offers similar opportunities for moving across disciplines, and sustainability research and teaching can help unify a campus around a shared sense of purpose.

Teaching sustainability helps students understand the importance of protecting the environment and natural resources for future generations. It provides them with the tools necessary to make informed decisions about their lives and their impact on their communities. Sustainability education can help students to recognize, understand and address social and environmental justice problems. Learning these skills prepares students for career success and responsible citizenship. Sustainability literacy helps empower students to participate effectively in civic dialog. And in preparing their students for the future, universities have increasingly recognized that many future jobs are sustainability jobs. Employers seek candidates with sustainability competencies, making sustainability education crucial to workforce development. Many industries’ fastest-growing segments are sustainability-oriented (e.g., renewable energy, organic agriculture, green buildings, and electric vehicles). In a globalizing world of limited resources, universities play a vital role in preparing students to meet future sustainability challenges through teaching about sustainability.